General Ruby on Rails Problems and Takeaways

Published Last updated loading views

Welcome to the last part of my Ruby on Rails Patterns and Anti-Patterns series. It’s been quite a ride writing and researching all of these topics. In this blog post, we’ll go over the most common problems I’ve encountered when building and shipping Ruby on Rails applications through the years.

The ideas I’ll go through here apply to almost anywhere in the code. So consider them as general ideas, not something related to the Model-View-Controller pattern. If you are interested in patterns and anti-patterns related to the Rails MVC, you can check out the Model, View, and Controller blog posts.

So let’s jump into general problems and takeaways.

Selfish Objects (Law of Demeter)

The Law of Demeter is a heuristic that got its name when a group of people worked on the Demeter Project. The idea is that your objects are fine as long as they call one method at a time and don’t chain multiple method calls. What this means in practice is the following:

# Bad

song.label.address

# Good

song.label_addressSo now, the song object no longer needs to know where the address comes from — the address is the responsibility of the label object. You are encouraged to chain only one method call and make your objects ‘selfish’ so that they don’t share their full information directly but through helper methods.

def Song < ApplicationModel

belongs_to :label

delegate :address, to: :label

endYou can go ahead and play around with the options that delegate accepts in delegete’s docs. But the idea and execution are pretty simple. By applying the Law of Demeter, you reduce structural coupling. Together with the powerful delegate, you do it in fewer lines and with great options included.

Another idea that’s very similar to the Law of Demeter is the Single Responsibility Principle (or SRP for short). It states that a module, class, or function should be responsible for a single part of a system. Or, presented in another way:

Gather together the things that change for the same reasons. Separate those things that change for different reasons.

Folks can often have a different understanding of SRP, but the idea is to keep your building blocks responsible for a single thing. It might be challenging to achieve SRP as your Rails app expands, but be aware of it when refactoring.

When adding features and increasing the LOC, I’ve found that folks often reach out for a quick solution. So let’s go through grabbing the quick fix.

I Know a Guy (Do You Need That Ruby Gem?)

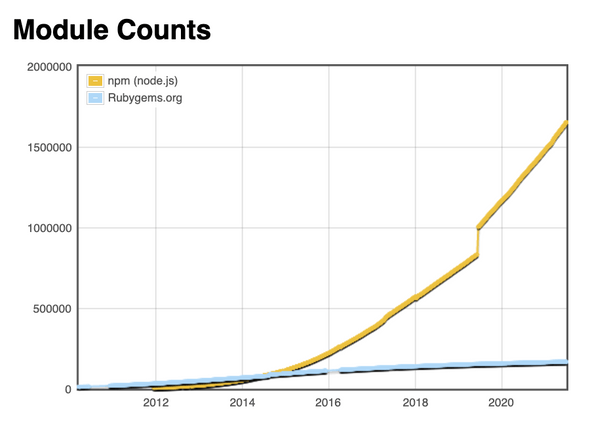

Back in the day when Rails was a hot topic, there was a boom in open-source collaboration, with new Ruby gems popping up on every corner (like it is nowadays with all the emerging JavaScript libraries, but on a much smaller scale):

Anyway, a common approach was to find an existing gem to solve your problem.

There’s nothing wrong with that, but I’d like to share some bits of advice before you decide to install a gem.

First, ask yourself these questions:

- What portion of the gem’s features are you going to use?

- Is there a similar gem out there that is ‘simpler’ or more up-to-date?

- Can you implement the feature you need easily and with confidence?

Evaluate whether it’s worth doing the implementation if you don’t plan to use the whole array of gem features. Or, if the gem’s implementation is too complex and you believe you can do it more simply, opt for a custom solution.

Another factor that I consider is how active the gem’s repository is — are there any active maintainers? When was the last time a release happened?

Another thing to watch out for is the gem’s dependencies. You don’t want to get locked into a specific version of a dependency, so always check the Gemfile.spec file. For this case, always consult the .

You should also watch out for the gem’s dependencies. You don’t want to get locked into a specific version of a dependency, so always check the Gemfile.spec file. Consult the RubyGems way of specifying gem versions.

While we’re on the topic of gems, there is a related idea that I’ve encountered: the ‘Not Invented Here’ (or NIH) phenomenon that applies to the Rails/Ruby world. Let’s see what it’s about in the next section.

Not Invented Here (Maybe You Need That Ruby Gem after All?)

In a couple of occurrences in my career, I had a chance to experience people (me included) fall for ‘Not Invented Here’ syndrome. The idea is similar to ‘reinventing the wheel’. Sometimes, teams and organizations do not trust libraries (gems) that they can’t control. Lack of trust might be a trigger for them to reinvent a gem that is already out there.

Sometimes, experiencing NIH can be a good thing. Making an in-house solution can be great, especially if you improve it over the other solutions out there. If you decide to open-source the solution, that can be even better (take a look at Ruby on Rails or React). But if you want to reinvent the wheel for the sake of it, don’t do it. The wheel itself is pretty great already.

This topic is quite tricky, and if you ever get caught in such a situation, ask yourself these questions:

- Are we confident that we can make a better solution than existing ones?

- If the existing open-source solution differs from what we need, can we make an open-source contribution and improve it?

- Furthermore, can we become the maintainers of the open-source solution and possibly improve lots of developers’ lives?

But sometimes, you just have to go your own way and create a library yourself. Maybe your organization doesn’t like licensing an open-source library, so you are forced to build your own. But whatever you do, I’d say avoid reinventing the wheel.

Lifeguard on Duty (Over-rescuing Exceptions)

People tend to rescue more exceptions than they originally aimed for.

This topic is a bit more related to the code than the previous ones. It might be common sense to some, but it can be seen in the code from time to time. For example:

begin

song.upload_lyrics

rescue

puts 'Lyrics upload failed'

endIf we don’t specify the exception we want to rescue, we will catch some exceptions that we didn’t plan to.

In this case, the problem might be that the song object is nil. When that exception gets reported to the error tracker, you might think that something is off with the upload process, whereas actually, you might be experiencing something totally different.

So, to be safe, when rescuing exceptions, make sure you get a list of all the exceptions that might occur. If you can’t obtain every exception for some reason, it’s better to under-rescue than to over-rescue. Rescue the exceptions that you know and handle the others at a later stage.

You Ask Too Much (Too Many SQL Queries)

In this section, we are going to go through another web development, relation-database problem.

You bomb the webserver with too many SQL queries in one request. How does that problem arise? Well, it can happen if you try to fetch multiple records from multiple tables in one request. But what most often happens is the infamous N+1 query problem.

Imagine the following models:

class Song < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :artist

end

class Artist < ApplicationRecord

has_many :songs

endIf we want to show a couple of songs in a genre and their artists:

songs = Song.where(genre: genre).limit(10)

songs.each do |song|

puts "#{song.title} by #{song.artist.name}"

endThis piece of code will trigger one SQL query to get ten songs. After that, one extra SQL query will be performed to fetch the artist for each song. That’s eleven (11) queries total.

Imagine the scenario if we load more songs — we’ll put the database under a heavier load trying to get all the artists.

Alternatively, use includes from Rails:

songs = Song.includes(:artists).where(genre: genre).limit(10)

songs.each do |song|

puts "#{song.title} by #{song.artist.name}"

endAfter the includes, we now only get two SQL queries, no matter how many songs we decide to show. How neat.

One way you can diagnose too many SQL queries is in development. If you see a group of similar SQL queries fetching data from the same table, then something fishy is going on there. That’s why I strongly encourage you to turn on SQL logging for your development environment. Also, Rails supports verbose query logs that show where a query is called from in the code.

If looking at logs is not your thing, or you want something more serious, try out AppSignal’s performance measuring and N+1 query detection. There, you will get an excellent indicator of whether your issue comes from an N+1 query. Here’s how it looks below:

Sum Up

Thanks for reading this blog post series. I’m glad you joined me for this interesting ride, where we went from introducing patterns and anti-patterns in Rails to exploring what they are inside the Rails MVC pattern, before this final blog post on general problems.

I hope you learned a lot, or at least revised and established what you already know. Do not stress about memorizing all of it. You can always consult the series if you are having trouble in any area.

You will surely encounter both patterns and anti-patterns because this world (and software engineering especially) is not ideal. That shouldn’t worry you either.

Mastering patterns and anti-patterns will make you a great software engineer. But what makes you even better is knowing when to break those patterns and molds, because there is no perfect solution.

Thanks again for joining and reading. See you in the next one — and cheers!

This article was originally posted on AppSignal

Join the newsletter!

Subscribe to get latest content by email and to become a fellow pineapple 🍍